For a few dollars more (1965) begins with a lone rider on a twilight plain somewhere in America. A gunshot rings out and the rider’s limp body falls from his horse. Leone’s sinister, opening joke is a surprisingly crude reminder – for those who might have forgotten the central concept of A Fistful of Dollars (1964) – that life is only worth what you give it. A hand-drawn gust of wind whips across the cracked earth, forming the title sequence in capital letters, accompanied by Ennio Morricone’s music (perhaps the best of the trilogy, certainly the most daring), severely stripped down with jaw harp and whistle, peppered with gunshots. Leone took a tight budget and made a masterpiece of anarchic fury, so he made something quite extraordinary for a few dollars more.

Before the bloody meal begins, an epigraph: “Where life had no value, death sometimes had its price. That’s why hitmen appearedThe first hitman, or hunter, we meet is Colonel Douglas Mortimer, played by Lee Van Cleef. He sits with a Bible spread out before him, suggesting a desire to travel undisturbed rather than an interest in the Scriptures. More importantly, as we shall see, Colonel Mortimer’s personal code is all that matters; Leone’s world is far too cruel to take amateurish interest in invisible, neglectful forces.

We’ve barely spent a few minutes with Colonel Mortimer when his burlap satchel unfolds, revealing an impressive array of killing machines, including a Colt Buntline Special to which he adds a ridiculous stock for long-range attacks. Needless to say, the gun is put to good use and Colonel Mortimer collects a bounty. The mustachioed man in black, the wily Lee Van Cleef, makes up one third of the film’s triumvirate.

Next we meet Manco (Clint Eastwood), which means “one-armed man” in Spanish, nicknamed the Man with No Name for publicity purposes, although he was previously called “Joe” in A Fistful of Dollars. Eastwood’s Joe in the previous installment was hardly amiable; Manco is an even less amiable version of the same character, talking less and doing more with arched eyebrows than most people do with Shakespeare. As his name suggests, Manco uses only his left hand, grabbing jacket lapels and punching saloon patrons while his other arm rests under his poncho. Only when the pursuit of a bounty requires shooting, which it invariably does, does Manco use his other hand. The result is spectacular, reduced to the essential movements: the hand comes out; the victims drop dead on the spot.

For a Few Dollars More is Sergio Leone’s most underrated film.

Sandwiched between two beloved classics, For a Few Dollars More is a superb film that deserves to be revisited.

The most crucial factor of For a few dollars more The third character we meet, El Indio (Gian Maria Volonté), has a whopping $10,000 bounty on his head. When we meet him, he’s imprisoned, sleeping under a sombrero, waiting for his accomplices to break him out. They do, of course. The ensuing escape is peppered with gratuitous violence directed at his captors and even at a poor idiot who helped El Indio escape. El Indio goes on the run, smokes weed, and hatches plans that would seem outlandish if he weren’t played by the wild-eyed Volonté. Beneath the smokey veils and shaggy gray hair is a calculating mastermind with enough enthusiasm—and scary henchmen, including Klaus Kinski as a hunchback—to make the El Paso bank heist plan work. As El Indio flees the past (all will be revealed, rest assured), he traces a predestined path that will lead him directly onto the paths of Colonel Mortimer and Manco.

Or A Fistful of Dollars offered a spaghetti pastiche of Akira Kurosawa Yojimbo (1961), here the remix is even more chopped and screwed, with aspects of Kuwabatake Sanjuro’s strategic mind spread across three goal-driven individuals. The story, however, is an entirely original and remarkably complex concept. Each character’s desires and very different methods of approach are highlighted as their separate paths briefly converge, meeting in mutually beneficial (and fate-ordained) arrangements before setting off again to wander the Wild West.

With barely a paragraph of background information, the three characters at the center of the film are perfectly represented. We understand everything we need to know about these men through the actions or the charged pauses between actions when thoughts materialize in facial contortions. Van Cleef, Eastwood, and Volonté are three of the best faces ever seen on the silver screen. We know what is coming long before the pieces are placed for the final confrontation, because the quick glances tell us far more, in almost imperceptible movements of plot and depth, than any number of exposition-laden action movies. Words, like life in Leone’s films, are cheap.

For a few dollars more is bracketed by two films that have received more attention in the last 60 years (give or take). Not only chronologically but stylistically, this contiguous masterpiece bears the hallmarks of its predecessor and signals the changes Leone would make in his later works. Leone’s stark, desolate imagery, born of necessity, remains the strength of these films, with some of the most striking close-ups offered in this middle sibling. Take, for example, the scene in which El Indio’s men inspect the Bank of El Paso while Colonel Mortimer sizes up the crooks. Meanwhile, across the way, Manco observes Colonel Mortimer through binoculars. For a scene composed mostly of faces observing their surroundings, the meticulousness is anything but soporific; it’s downright invigorating.

For many Sergio Leone fans, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly marks the moment when opera became mythological. But all the elements were present in For a few dollars morewho is taut as a tourniquet and moves with the conviction of a cold-blooded killer. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is the grand declaration of an artist in full control of his powers, this film serves as an informal farewell to a filmmaker who is more muddled, more filthy, but no less seductive. Leone would push the limits of palpable temporality in his next film and, finally, in Once Upon a Time in the West (1969). However, the incessant passage of time is present throughout this trilogy.

For those who haven’t seen it yet For a few dollars moreIt’s easy to guess what the story implies from his naked movements. These films, boldly made as if carved in stone, have become ingrained in our cultural memory and sense of Wild West narratives. Which makes them particularly great For a few dollars moreIt’s the details beyond the plot—the way each performer navigates well-known terrain. Through gestures, small exchanges, and cool This film invites us to contemplate a living world, where destiny opposes individual wills and destroys all hope. In the land of criminals and bounty hunters, the only winner is the one who has the chance to heal his wounds and prepare for the trial that will follow.

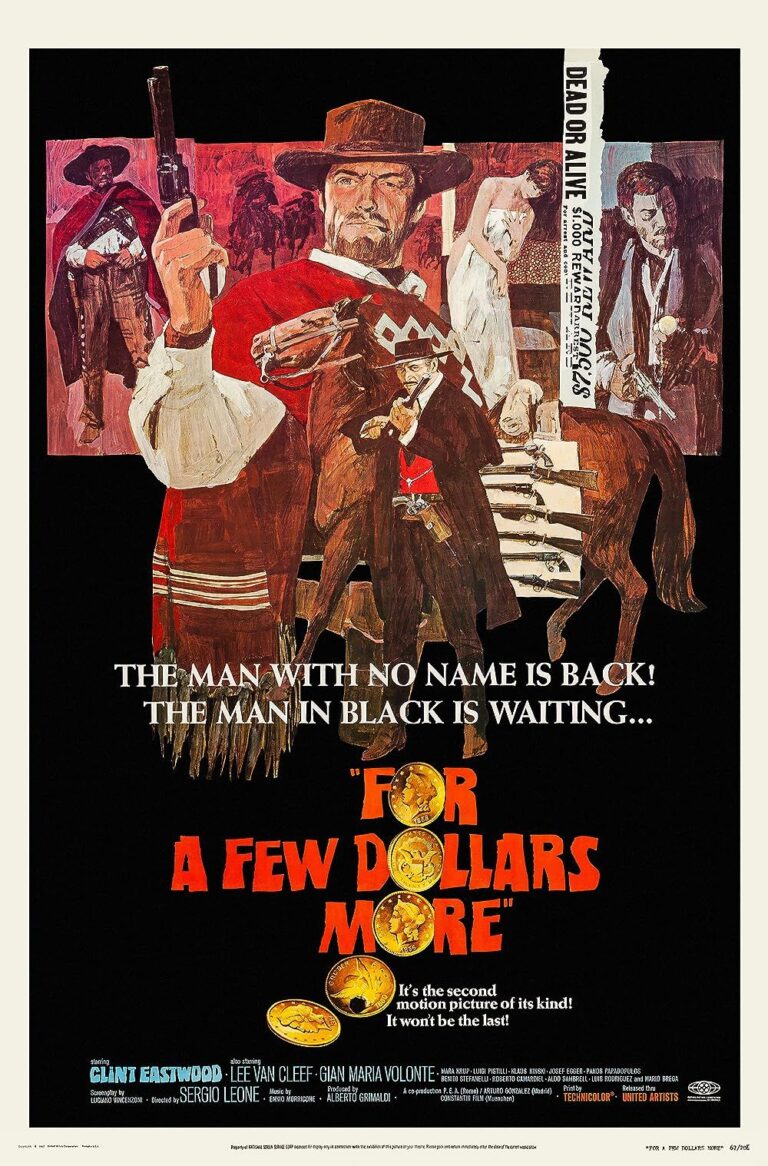

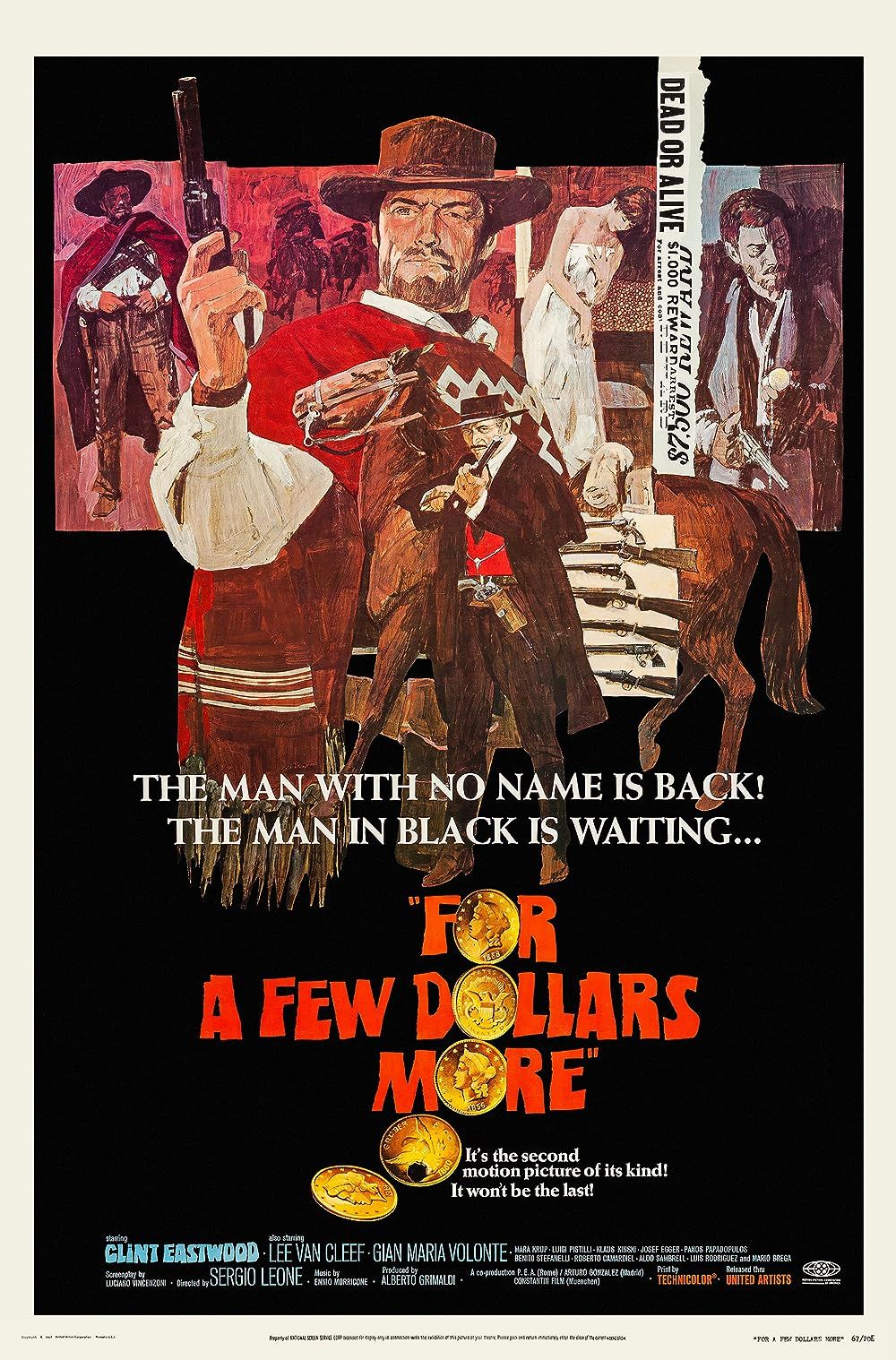

picture

big

For a few dollars more

Two like-minded bounty hunters team up to track down a Mexican outlaw on the run.

Starring Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef and Gian Maria Volonté, For a Few Dollars More was released on December 30, 1965 and directed by Sergio Leone.

Features

- Director

- Sergio Leone (Person)

- Release date

- 1965-12-30

- Casting

- Clint Eastwood (Nobody), Gian Maria Volonte (Nobody), Lee Van Cleef (Nobody)

- Rating

- R

- Runtime

- 2 hours 12 minutes

- Main genre

- Western (Genre)

- Genres

- Drama (Genre)

- Lee Van Cleef with a mustache and a grudge

- Clint Eastwood’s Manco is one of the actor’s best roles, almost silent

- Gian Maria Volonté is breathtaking in his portrayal of the deranged El Indio

- Leone’s impeccable timing gives even relatively quiet scenes a propulsive energy.

- Ennio Morricone’s music is a masterpiece with multiple moods

- Some of the peripheral characters are played by over-the-top actors who don’t fit comfortably into the film.