When Gene Roddenberry redesigned the USS Enterprise for a NEW generation of Starfleet officers, he wanted to make a very specific addition. In 2013 Sound effects issue, The A-Z of Star TrekMartina Sirtis explained why Gene Roddenberry told her he created USS Enterprise advisor Deanna Troi, “Gene [Roddenberry] “I came up with the idea for this character because he felt that in the 24th century, mental health should be as important as physical health.”

It’s a fascinating concept, because for people of Gene Roddenberry’s generation, psychology was not treated in the same way as it is today, although its reputation was obviously built over time. However, at the time of the original Star Trekor the original The Twilight Zone episodes, psychology rarely came into play in terms of a counselor who was there at all times to help the crew members with their problems.

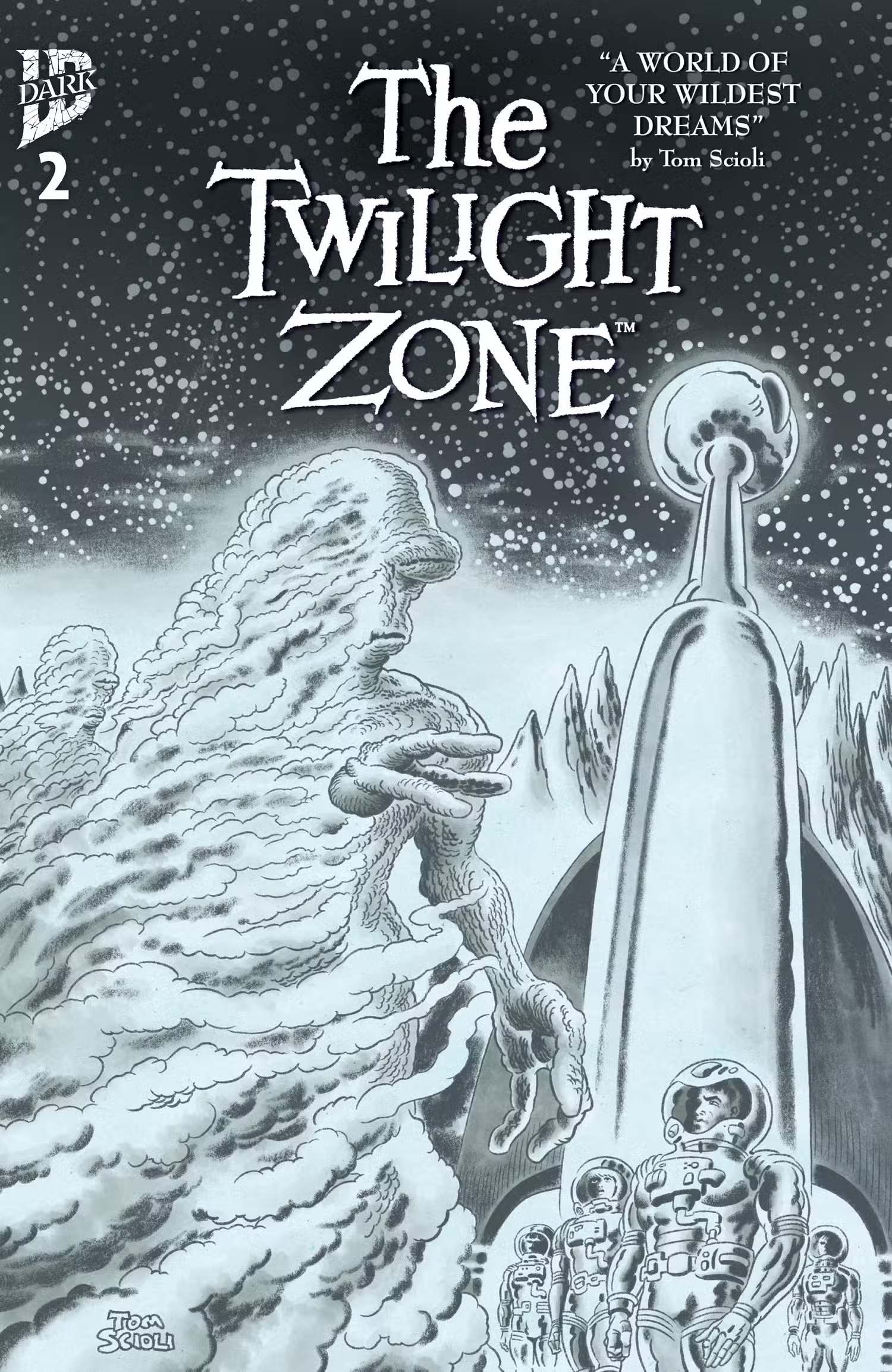

It is, however, interesting to note that in the latest issue of The Twilight Zone (#2), writer/artist Tom Scioli manages to craft an entire issue as a sort of homage to the powers of psychology… in SPACE!

The Twilight Zone Issue #2 comes from writer/artist/letter Tom Scioli, who is a brilliant comic book creator, and just out of the absolutely delightful IDW. Godzilla Monster Plays Theater series. Here he uses his distinctive storytelling skills to tell a story that wouldn’t seem so out of place in a classic. Twilight Zone story, only with a modern twist based on the importance of psychology in modern society, something that certainly LOOKS like what people in the 1960s probably would have LOVED to hear back then.

How does Scioli’s artistic style illuminate the story?

Tom Scioli is best known for his Jack Kirby-style illustrations, which he often uses to tell bold and expansive comic book stories. However, this is not always the case for his work, as he also does a good approximation of a number of “classic” comic styles, and this suits this tale perfectly, as it allows him to do, indeed, “talking head” scenes, but still distinctive ones.

You see, one of the problems with doing stories in the style of Rod Serling’s screenplays is that most of Serling’s stories had a lot of dialogue. This of course has to do with the very nature of making a regular television series in the late 1950s and early 1960s. You couldn’t afford to do a ton of special effects, so you had to build the drama through dialogue instead. Think classic “It’s a beautiful life” where the little boy controls his entire town. Yes, there were actually a lot more special effects in this episode than in most episodes, but in general horror is character driven.

Character-driven storytelling is very difficult to pull off for comics, because while a human actor can obviously make you care about a monologue, it’s much harder to hold people’s attention on that sort of thing in a medium where nothing moves, and you can’t rely on the charisma of your actors to sell the scene. This is where having an interesting art style like Scioli’s really helps, because it allows those dialogue-heavy pages to still read well, even with, well, you know, tons of dialogue.

These pages remind me a bit of the classic DC Silver Age sci-fi stories, where you would have artists like Gil Kane, guys who were so good at doing big, bold actions, and, because of the format (6-8 page stories in a sci-fi anthology), the artists would mostly just have to support the dialogue, because there was so much information that had to be “dumped” on the reader at once (I quote because, if you deliver the information well, it doesn’t really doesn’t count as “dump”).

Tim Burton’s 26-year-old gothic masterpiece continues with a new story and we have an exclusive sneak peek

A new comic resurrects the terrifying legend that Tim Burton resurrected years ago.

How did this second issue compare to the first issue?

As I noted in the first issue, one of the areas where this series stands out is that since it’s a comic book, it can do things that a TV show can’t do. This is an even more remarkable example of this sort of thing, as Scioli sends these astronauts on an absurd journey where they seem to run into a number of bizarre aliens. These are the kind of effects that the TV series could only DREAM of having in the series.

However, as we will soon learn, this is all a charade related to the very nature of psychoanalysis, and the question becomes: how much are you willing to sacrifice for your personal growth? And how much are you willing to give up to AVOID having to do the work on yourself? These are fascinating questions that transcend any history, but speak to the universal nature of The Twilight Zone.

Science fiction, at its best, is a case where the strange situations the characters face simply function as metaphorical representations of the struggles that exist within everyone, and that is very much the case in this story. Scioli is a talented writer/artist, and he does a wonderful job conveying these ideas in a charming and visually entertaining way. It’s a WEIRD comic at many points, but the end result is something that really has weight, and Scioli’s visual storytelling is one of the main reasons it all works together.

The unusual visual aspects of the story make it a little different from a “typical” story. Twilight Zone story, but the elements that support these visual aspects are things that Serling could easily have addressed in 1962, although perhaps not in a QUITE psychology-forward-thinking way.

Source: IDW