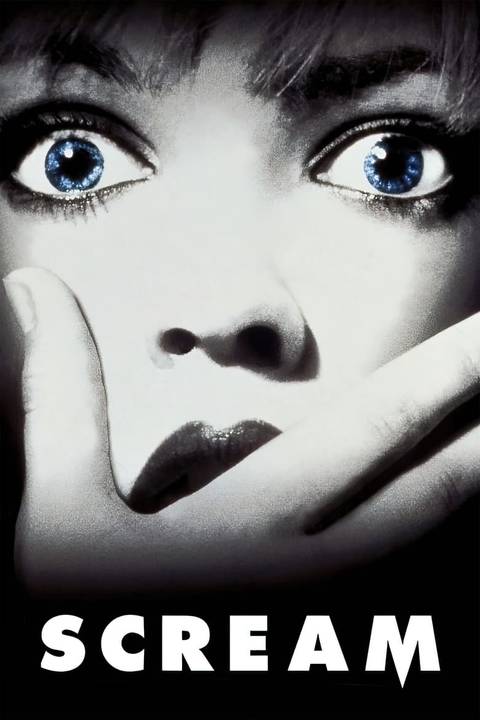

When Shout was first released in 1997, some audiences weren’t sure what to make of it. Was it a horror? A parody? Satire? The answer is, technically, everything. Wes Craven’s cult classic used and mocked classic slasher tropes, with ignored warnings, unlocked doors, and open windows used to critique the genre’s predictability. But what worked for the film, and a big reason for its timelessness, was that Craven used these tropes effectively alongside the horror, not as a replacement for it. Part of this effectiveness came from the film’s use of gory and inventive kills, shocking enough to satisfy horror fans while emphasizing the formal nature of slasher violence.

What many viewers may not realize, however, is that Shout was initially rated NC-17 for its graphic and extensive death scenes, forcing Craven to cut several moments to achieve an R rating and reach a wider audience. Story-wise, the NC-17 version isn’t that different from the R version, just with a bit more blood, guts, and drawn-out scenes. It is, however, slightly more effective in terms of overall commentary on slashers. And nowhere is this stronger than in the film’s original opening scene.

The original opening scene of Scream was much more graphic

ShoutThe opening scene of is considered one of the greatest in cinema history. Beyond the unexpected death of Drew Barrymore, who was originally presumed to be the star of the film, the scene perfectly sets up the events of the film and features the stalking Ghostface on the phone as he tortures poor Casey and Steve. Overall, the two scenes are almost identical. Casey receives a series of phone calls from Ghostface, who torments her and forces her to take a horror movie quiz, later revealing a tied-up Steve on the patio.

After Casey gets the question wrong and Ghostface kills Steve, the R-rated scene shows a close-up of Steve’s face before zooming out to briefly show his drained body. The NC-17 version, however, extends the moment. Although the disembowelment itself is not shown, there is a longer shot of Steve’s intestines leaking from his body, followed by a lingering close-up of his bloodied face. Likewise, the reveal of Casey’s body is also extensive.

In both versions, Casey’s parents arrive home to find the house ransacked and full of smoke, as they frantically search for their daughter. Grabbing the phone to call the police, Mrs. Becker hears Casey on the other end, opens the door and sees her daughter hanging from a tree in the front yard. The R-rated version quickly zooms in on a close-up of Casey’s body, before abruptly cutting to the next scene. The NC-17 version zooms in much slower, lasting about ten seconds longer, showing Casey’s mutilation in greater detail.

Although the changes are minimal, the NC-17 version is arguably the best. In the 90s, graphic violence became more explicit, with films like Se7en, Event Horizon, and even candy man pushing the limits of what the general public could handle. The horror grew bloodier and the violence became more confrontational, but in many cases it also began to lose its meaning. Craven was an expert on commentary.

The last house on the leftwhile still one of the most disturbing films ever made, was a commentary on public desensitization to violence and exploitation. In the same way, The hills have eyes was a social commentary on civilization against savagery, classism and cruelty. Seriously underrated, many of Craven’s films combined horror with some form of commentary.

Although more satirical than The hills have eyes And The last house on the left, screams still carried this same philosophy into the modern era. Craven wanted viewers to recognize how horror had evolved, how formulaic it had become, and why it still worked despite that. The violence in Shout was deliberate in both critiquing and celebrating the genre’s most familiar tropes. This is why the NC-17 montage, with its slower, more visceral moments, arguably matches Craven’s vision more closely.

In the R-rated version, those few seconds of restraint are enough to lessen that impact. The murders still work overall, but the NC-17 version forces the viewer to confront the violence that horror has long taken for granted.

NC-17 version of Scream features longer kills

The opening scene is the biggest difference between the two versions, but several other murders are also longer in the NC-17 original. Tatum’s death is slightly longer and more graphic, with the R-rated version cutting off as soon as his face hits the top of the garage door frame, while the NC-17 version lingers slightly longer to show his crushed face.

Similarly, Kenny’s death does not immediately cut off Sidney’s reaction, like in the R-rated version, but instead shows him slowly bleeding out for a few more seconds. The final scenes are also slightly longer. When Billy stabs Stu repeatedly in the kitchen, the R-rated version immediately cuts to Sidney’s reaction, with just the sounds of the knife and Stu’s moans in the background. The NC-17 version actually shows Billy stabbing him, with a pool of his blood on the floor next to Sidney’s father.

Overall there are very few changes, just slightly less extensive scenes and graphical shots. But the story behind these cuts is almost as interesting as the film itself. According to multiple reports, Craven fought for months with the Motion Picture Association (MPA) to avoid an NC-17 rating, submitting at least nine different edits before the board finally accepted an R. Nearly every one of Ghostface’s victims had to be cut, not so much for what was shown, but for how long the camera lingered on the aftermath.

Craven, who had already experienced a similar ordeal with The last house on the left two decades earlier, was increasingly frustrated by what he saw as arbitrary censorship. “We never give names, we never know who saw your film,” he said later, “and very often, it’s a different group each time. So it’s quite horrible to deal with.”

Some of the committee’s objections bordered on the absurd. W. Earl Brown, who played cameraman Kenny, recalled that the MPA asked Craven to shorten his character’s death shot because his “expression was too disturbing.” Likewise, the now-iconic sequence in which Billy and Stu stab each other was heavily edited to remove visible contact with the knife. Editor-in-chief Patrick Lussier explained that the MPA even rejected Billy’s famous line “Movies don’t create psychopaths, movies make psychopaths more creative!” “, insisting that it be deleted because it was “too truthful.”

After repeated re-releases failed to gain approval, it was producer Bob Weinstein who finally saved Shout with an NC-17 rating. In a final phone call, he convinced the MPA that the film was “a comedy, a satire” of horror, and not a simple slasher. This argument worked, and with the R rating ultimately granted, Shout was released in December 1996. Of course, the film defied all expectations.

What could have been another body count became a genre-defining phenomenon, reigniting mainstream interest in slashers and reshaping horror for a new generation. And even though most viewers have only seen the R-rated version, the elusive NC-17 edit remains the one that best reflects Craven’s vision.

- Release date

-

December 20, 1996

- Runtime

-

112 minutes

- Writers

-

Kevin Williamson

- Producers

-

Bob Weinstein, Cary Woods, Cathy Konrad, Harvey Weinstein

-

David Arquette

Dewey Riley

-

Neve Campbell

Sidney Prescott